|

As we make the transition to Common Core, I am encouraged by many of the conversations I have been having with teachers - both at my site, and beyond. Whereas prior to CCSS many said they didn't "have time to integrate technology," I am now beginning to hear much more encouraging statements, things like - "Hey. You know that Google Docs thing? Show me." The #EdTechGeek in me is turning cartwheels and leaping over tall building to be able to share the power of GAFE, of giving students choice, of allowing them to create instead of consume. That's some pretty awesome trickle-down tech usage, and for the most part I am encouraged by the willingness of other professionals to try new things. But there is one conversational tack that is driving me nuts: "Hey. Common Core testing means that we should bring back keyboarding classes. Let's get right on that!" This is how I feel when someone makes this suggestion: Let's be clear: Keyboarding classes are NOT a silver bullet that will magically transfer students into digitally literate learners who are prepared to face the Common Core test. The conversation really needs to be about how our instruction needs to change, across grade levels, in all departments. To me, Common Core is not about examining what we can add on the existing system in order to make it compliant. Common Core is about thinking outside of the box, and getting our students to think outside of the box. It's about reviving what's best in terms of our pedagogical options and saying goodbye to the worst. Shouldn't we be making instructional decisions based on what's best for kids? Shouldn't the conversation center around how to meet CCSS by redesigning the way we offer students learning opportunities in class? Shouldn't we consider the SAMR model and decide what it will take to reach a level of redefinition? Shouldn't we be bringing back Project-Based Learning, planning for inquiry, and taking a constructivist approach to learning? Instead, I often find that the CCSS transition often gets boiled down to keyboarding. Predictably, at the secondary level the blame then gets shifted to elementary teachers for not providing vital keyboarding skills, and before you know it - professional inertia is reached. When the best suggestion we've got is to reinstate keyboarding classes, that is a suggestion motivated out of fear. Yes, it's scary to take the practice tests on Smarter Balanced and realize that kids have instructional needs that aren't being met. Yes, Common Core will require systemic change across content areas - which for some folks will be more painful than for others. But how can we be indignant when students lack typing skills if we never integrate technology into the core curriculum? That is like being surprised when you try the same thing over and over and keep getting the same results. Albert Einstein once said, "We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used to create them." The visionary passion around which I have designed my classroom - everything from the physical arrangement, to the climate, to the learning activities, to the tech - is to help prepare my students for their future. I want to enable them to create their own goals and dreams, then equip them with the skill set that will enable fruition. In Room 208, we use iPads and Chromebooks daily and we allow BYOD for students who would like to use their own device with school wifi. My students close read in eBackpack and Google Docs, then create movies, record podcasts, screencast their thinking, design digital posters, use evidence to support their conclusions, and write like investigative reporters. None of that was accomplished with a keyboarding class. If a school site has limited technology resources, then it becomes even more important to use those resources in core classes, as opposed to reserving them in a lab setting for the express purpose of teaching keyboarding. For a school like mine, which services 1,500 students and is approaching a 2:1 student/device ratio, there are definitely better options than reserving technology to teach a keyboarding class. What is your school doing to prepare for Common Core? What do you think about how students develop keyboarding skills? Share your thoughts below or continue the conversation on Twitter: @Packwoman208.

1 Comment

We are a little over a month into the school year here in PSUSD, and I realized today while teaching my morning block of 6th graders that as a class we have finally hit our stride. This is my second year as a BYOD teacher, last year's pilot having been a resounding success. (Thank goodness!) This is also my first year teaching fully Common Core lessons, which has been an easier transition than expected. Since I've been approached quite bit recently, both at my school site and via Twitter, regarding the Common Core lesson planning process, I thought I'd take a moment to blog about it to give others a starting point. Unpack the standard and begin with the end in mind. The first thing I do when planning a CCSS lesson is unpack the standard to decide what skills are expected to reach mastery. There are a lot of fantastic resources on the web that can help you with this step so that you don't have to reinvent the wheel. A few of my favorites are these unpacked "I Can..." statements in student-friendly language and the unpacked ELA Common Core Templates from the Tulare County Office of Education. Use these to help establish your learning targets. Following the unpacking process, consider what the endgame is for students. What will they produce? What will they do to show their learning along the way and once the sequence of lessons is complete? Will they be writing arguments? Engaging in a debate? Recording podcasts? Producing a movie or telling some other kind of digital story? The importance of these questions can not be overstated. Consider the CCSS Shifts, then begin building a series of lessons. There are 7 key shifts in Common Core ELA instruction, which are important to remember. I've outlined these shifts on the following Haiku Deck: When lesson planning, I generally follow the cognitively guided instruction model, which is a gradual release of control until students are able to work independently. Why do I follow this particular model? Because it was adopted universally by my district and that is the expectation. However, something that I have discovered is that, while some feel this instructional model lends itself best to direct instruction, it can also be adapted for inquiry and project-based learning. The concept is, essentially: "I do. We do. You do together. You do independently." The phases of instruction can be rearranged to suit the style of lesson. So, for an inquiry-based lesson, you may choose to lead with the "You Do Together" portion as groups problem solve by brainstorming possible solutions; the "I Do" portion may be limited to simply issuing instructions to express the parameters of the investigation. Create opportunities for communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity. Because my classroom is comprised of so many English Language Learners, providing opportunities for students to work together to communicate their ideas with an authentic audience is important. A few days ago, in the midst of an ELA unit based around the topic of Japanese internment during WWII, my students analyzed primary source photos in groups. I pulled the images from the Library of Congress Japanese internment collection, and had kids rotate through five different centers in groups. Each center had a different image they had to analyze. Students used the Primary Source Analysis Tool (also from the Library of Congress), on which they recorded observations, made reflections, and asked questions about each image. (The suggestions on this document were helpful in terms of getting group conversations started.) Group conversations were dynamic and students were highly engaged because they had previously read and annotated the full text of Executive Order 9066 and Instructions to Japanese-Americans on Bainbridge Island. Following the rotations, students used sentences frames to help them write a podcast about their favorite image from the day and how it connected to their reading. Here is an example podcast one of my students created using the AudioBoo app:

Recognize that the CCSS is student-centered. When I first started teaching, I used to lose my voice by the end of the day because I did so much talking throughout each class period. Nine years later, this is no longer an issue because my students work harder than I do while they are in class. I want to make sure that their learning is genuine, that they are completely engaged in the process, that they have real choices about how to express mastery, and that their brain cells get a workout without realizing that it's "work."

Ultimately, the CCSS transition will be easier for some than others. Districts and school sites will establish different mandates, I am sure. Teachers will likely receive conflicting messages, as is generally true in any kind of new implementation. The best advice I have for anyone who is making the transition is to hold fast to your PLN, ask questions, collaborate, and keep what's good for students at the forefront of your decision-making process. What's your best CCSS lesson planning recommendation? What tools are essential to your CCSS plans? Please comment and share, or continue the conversation on Twitter.  It never ceases to amaze me just how much good stuff is out there on the Internet, in terms of tech tools that are useful in the classroom. While attending #CUE13, my hands-down favorite session was called "Get SLAMMED with Google" presented by some pretty awesome Google Certified Educators. (Note: On the Educative Gradient of Awesome, these people are off-the-grid wowzers!) They had plenty of useful recommendations, tips, tricks, etc. - but what I really appreciated learning about was a neat little tool called Docs Story Builder. It is such a great find that I went straight back to my classroom the Monday after CUE and put it to work! What is Docs Story Builder? Docs Story Builder is a Google web app that allows users to create conversations in a simulated Google Docs collaborative environment. Check out this silly sample from the Docs Story Builder home page: Tell Me a Story: The Process To implement this brand-new-to-my-classroom tool, I gave my students a quickie tutorial that lasted about a minute, then gave them five minutes to mess around and explore. Because the interface is super easy to use, this was more than sufficient time and generated a lot of excitement. In case you're a fan of how-to videos, here's a brief tutorial, which is actually longer than the prep I gave my students:  Docs Story Builder integrated seamlessly into Language Arts. Students had just finished reading the short story, "What Do Fish Have to Do With Anything?" by Avi. The focus for this reading selection was symbolism, but we also spent quite a bit of time talking about characterization. In the story, a boy named Willie asks his mother difficult questions about life and unhappiness after encountering a homeless man on the street. Students were able to engage in rich discussion because of the complexity of the content. To extend that interaction, I asked students to write a conversation between Willie and his mother, Mrs. Markham. Students had to stay true to the characterization of each as seen in the text, and include a text-based controversial statement made by the character of Mrs. Markham. Here are a few of the Docs Story Builder projects they created:

Reasons Why You Should Heart Docs Story Builder:

Have you used Docs Story Builder in your classroom? I'd love to hear what you asked your students to create - or better yet, see some examples! Comment on this post or hit me up on Twitter (@Packwoman208) to continue the conversation.

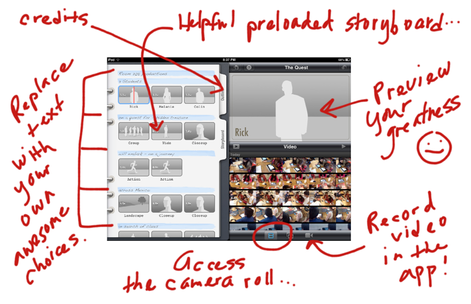

Happy Story Building! One of the reasons I love teaching 6th grade at a middle school is that I get to watch my students slowly develop all sorts of awesome qualities over the course of a year, including wittiness and a dawning understanding of repartee. In September, they’re so overwhelmed by the middle school learning curve, they don’t quite register all of my lovingly sarcastic quips, but after the holidays, it’s the long haul toward becoming a teenager – and something never fails to unlock the Sarcasm-Center of their brain. That’s when learning gets really fun, because there always seems to be plenty of laughter to accent the “a-ha!” moments. So, today, when one of my girls said, “Hey, Mrs. Pack. Are you sure this is ELA, or did you just decide we could take some time off?” I almost burst out laughing, thinking she was being sarcastic. However, when I realized that this twelve year old was entirely serious, as evidenced by her truly bewildered expression, I decided to lay my best possible answer on her: “Well. Learning is supposed to be fun, right? This must be ELA, then.” What was her reply? A hug. You might be wondering what the heck we did in Language Arts this week that would elicit such a grateful response… Answer: We made movies.  My students have been reading a fantastic book of short stories by Gary Soto called, “Petty Crimes.” The short stories all take place in the same neighborhood, but feature different characters. Since most of my students are Hispanic, they love Gary Soto’s writing and they especially love his characters, which include wannabe cholos, fierce cholas, endearing abuelitos, and menacing tias. When I noticed one of my classes was having trouble isolating the main events of each story, tending to focus as much on details as major plot shifts, I decided to have the kids retell their favorite chapter of “Petty Crimes” using iMovie trailers on a couple of iPads. First, I divided students into groups by drawing names out of a hat and had each group choose their favorite short story. Then, everyone worked together to choose the most appropriate trailer template for their project; this led to a very cool, totally organic discussion about how the preset iMovie music and graphics in the trailers communicate a certain mood and tone. Students were very successful in making appropriate choices, all of which resulted from fantastic group conversations. Since digital storytelling is still a fairly new concept for this class, I delivered a quick lesson on film angles. Next, everyone worked together to retell their story in words and planned the action they needed to film to fill in all of the video clip spots in the trailer storyboard. The fact that the trailers have limited space for words and images increased the need to retell stories effectively, choose wording carefully, and search for powerful synonyms. iMovie for iPad was a breeze for students to learn, and the biggest challenge was helping students remember to film with their iPad in landscape. Over the course of the week, we spent about 15-20 minutes per day working on our trailers. Students brought in an insane amount of costumes and utilized my prop box to help them tell their stories more realistically; even in 6th grade, kids love to dress up. In the end, not every movie was perfectly filmed, but all of the students managed to successfully retell the major events of each story – and they had an absolute blast! To finish out this blog post, I thought I’d share a few student products: Comments? Questions? Feel free to leave a comment or email me at jpack@psusd.us.Download my iBook: Digital Storytelling: Connecting Standards to Movie-Making

Take my iTunes U course: Digital Storytelling: Film Challenges |

Author: Jessica PackCalifornia Teacher of the Year. CUE Outstanding Educator 2015. DIGICOM Learning Teacher Consultant. 6th Grade Teacher. Passionate about gamification, Minecraft, digital story-telling, and fostering student voices. Download:Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed