|

James Portnow contends that the goal of games should be to facilitate or enable learning, as opposed to overtly educating players. In his video, he talks about how tangential learning occurs when people are interested in a topic and invested in learning more. This coincides with Jane McGonigal’s assertion that games provide a sense of epic meaning that increases the investment of players over time, because they believe their work in the game is truly meaningful. In an educative context, perhaps the most important thing to remember about gamifying our classrooms is that the element of choice is essential. Self-direction stimulates a greater sense of intrinsic value than a universal approach to learning about a topic. Now, some concepts will be best taught overtly, but there are many more concepts that can be developed indirectly.

Portnow says, “If we’re interested in something, we’ll have an easy time learning it. The problem with the educational approach is that it tries to jazz up a topic we just don’t care about, rather than trying to get us engaged in a topic and care about it in a personal way. But video games have a huge advantage here. We inherently care about what we’re doing when we play games. The enthusiasm is already there. The game designer just has to channel it.” This quote is especially powerful to me because the teacher is essentially the game designer. Our biggest challenge in the classroom every day is getting kids to care about what we’re learning and engage with content in a meaningful way. Portnow goes on to say that the whole idea of effective game design is “Enhancing the experience without getting in the way of the fun…Games, above all, should be fun.” I think many educators – particularly administrators – would argue that the content should be front and center at all times, which conflicts with Portnow’s points of view. Perhaps that is the value of teacher-trailblazers; they have the job of challenging traditional thought. As I continue to refine my understanding of gamification, I have questions that require further exploration. Pressing questions for me include the following:

0 Comments

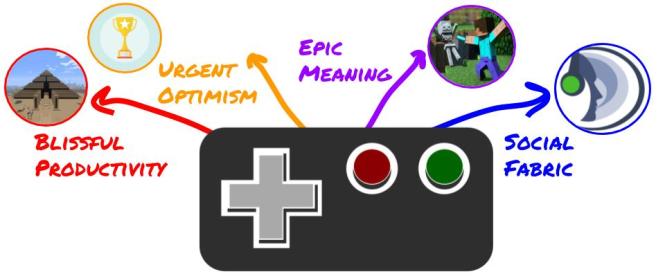

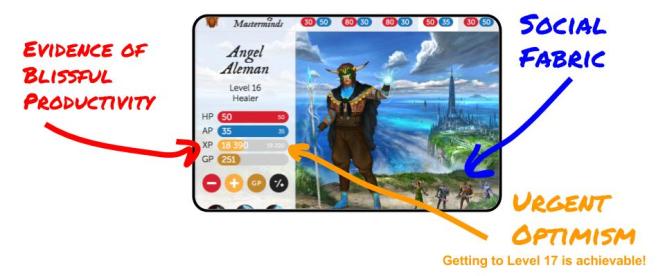

When I checked 3D Game Lab this morning, I was so excited to see the “Games Can Make the World Better” quest appear in my available lessons! I have long been a fan of Jane McGonigal and this particular TED Talk. In fact, my students even watch this TED talk and complete document-based questioning during our unit on coding! McGonigal makes some solid arguments for the incredible impact that games have our society and the potential of games to create an even larger impact over time. Gaming provides an opportunity to learn skills such as collaboration, creativity, problem-solving, and critical thinking – all of which are embedded in gameplay as opposed to overtly instructed. To further to impact of games, players engage in tangential learning because they enjoy the activity and have a desire to educate themselves on related concepts as a result. McGonigal cites Gladwell’s 10,000 hours theory as evidence that gamers are actually educating themselves on gaming principles to the extent that they are virtuosos. She claims that gamers develop a sense of urgent optimism while fostering a strong social fabric. They engage in high levels of blissful productivity, which in turn contributes to a sense of epic meaning associated with their gameplay. From an educative standpoint, this translates into learners who are high motivated, able to collaborate, persevere through difficult tasks, and make greater connections between themselves and the world. Many of those behaviors are qualities teachers seek to instill as per the CCSS Standards for Mathematical Practice and the Common Core Habits of Mind. Games constantly, consistently acknowledge player progress, which I think plays a big part in making gaming a compelling experience. Gaming interfaces often include earning XP and provide progress bars for monitoring one’s advancement through levels of gameplay. Often, there are also badging systems and/or a way to earn advanced equipment or perks. In some games, a player’s avatar is reflective of their accomplishments in the game, which can provide motivation for players to continue.

In the classroom, we often give immediate feedback during class discussion, but not nearly enough to be truly motivating. Added to that, there is often a pretty hefty turnaround for grading assignments, particularly at the secondary level when teachers have 150+ students. Feedback from teachers might not even be particularly valuable or meaningful to some students, typically those who are not academically oriented. They are not motivated by grades because there is no epic meaning attached. For these students especially, there is no larger academic story to be told, no way to “win” school and therefore fewer reasons to try. Gamification presents a unique opportunity to layer gaming principles over curriculum, as seen in the quest-based lessons we are experiencing in EDTECH 532. Even the use of a tool like Class Craft, where students can customize avatars and earn XP for academic tasks, makes school feel more like a game. |

Author: Jessica PackCalifornia Teacher of the Year. CUE Outstanding Educator 2015. DIGICOM Learning Teacher Consultant. 6th Grade Teacher. Passionate about gamification, Minecraft, digital story-telling, and fostering student voices. Download:Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed