|

A student cried in my classroom yesterday. This is not an entirely unusual experience, since we get teary eyed quite often while reading some of our favorite novels - like when Salva, a Lost Boy refugee in "A Long Walk to Water," goes back to war-torn South Sudan to build wells for his people. Or in "The Tiger Rising" when Rob, a troubled boy whose mother died, finally opens up to his father and lets all of his emotions pour out. Oh, and lots of kids also got a little misty while reading "Rules," wherein a boy with cerebral palsy makes his first-ever friend. So, crying is sometimes just part of the larger context of our classroom, and I've been known to shed tears, too. No matter how many years I've read some of these books with my classes, it always feels special to connect not only with literature, but with one another, too. Yesterday was different.

This time, one of my students stayed after school to work on a digital storytelling project that she is undertaking. One of my language arts students and also an after school AV Club devotee, I've been encouraging this wonderful young lady all year. Ever since she proudly told me that she is a folklorico dancer on the evenings and weekends, I've enthusiastically urged her to share her story. I know that as teachers we're not supposed to earmark favorites, because they are all our kids, but I am so touched by this girl and her family. With immigrant parents and a house on the other side of the freeway, her family makes time to drive her to school every morning. Super studious, constantly in motion, and quite a chatterbox, she always has stories to share - like the morning after President Obama's executive order regarding immigration. She came right up to me, smiled brightly, and proclaimed, "Did you hear? The president forgives us and says we can stay. My mom cried last night, because she is so happy."

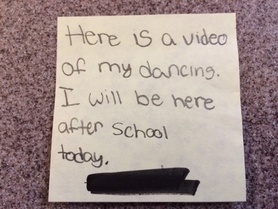

This student has worked for a week on writing a script about folklorico. As her guide, my job at this phase of the production process is to offer suggestions on storytelling. I began with the positive aspects of her topic, complimented her storyboard ideas, and affirmed that I thought she had a wonderful story to share. Then, I tried to explain the difference between "showing" and "telling" when writing a script. She nodded vigorously, but still seemed confused. So, I referenced an entry from Julie Barda's class in last year's DigiCom Film Festival and pulled it up to use as an anchor video: Our Story from DIGICOM Productions on Vimeo. I think we only watched about 45 seconds before she started crying. I immediately paused the video, worried. Worried that I had somehow offended her, worried that she was discouraged, worried that I wasn't being gentle enough in my critique. For the first time ever, I didn't know what to do or say when confronted with tears. I decided to wait her out, offer Kleenex, and listen. It was a good strategy. "This is a good story," she told me. "It makes me think of my mom and my experience in kindergarten. It makes me think of my culture and how proud I am of what my family has done." "Good," I responded. "You should absolutely feel proud to be who you are." "And, I get it now," she said. "I understand what you mean about my script. But I don't know how to fix it." After a few beats, I asked her why she dances. I asked her to think about what she feels when she dances and what keeps her showing up at practice every week. I asked her why the long hours, the elaborate costumes, and the music are so appealing when other kids her age tend to focus more on Instagram and Snapchat. More tears welled up in her eyes as she considered her answer. "Because. I forget everything else in my life, all my trouble and all my worry. I don't think about anything but the music and the steps and I feel joy." And that perfect revelation was the heart of her story. Sometimes, as a script writer, there are quiet moments when everything comes together and the story works out just right. The key to digital storytelling is to write from the heart, and some of the most compelling stories that can be told are the ones about ourselves. This morning, I arrived at work a few minutes later than usual. On my desk, in a zip lock bag, there was an SD card with a sticky note:

2 Comments

2/28/2015 01:43:40 am

This is a lovely story, told by a loving teacher, about the love of a girl and her family. Thanks so much, for sharing. BR

Reply

Samantha Rodriguez

5/18/2015 01:31:47 am

OMG thank you so much Mrs. Pack. You always made my day. I can trust you because I have never met a teacher that I can explain my problems, feeling, emotions, and eximents. Thank you for always being their for me and never letting me go. I can say that your my best friend because even though you are older than me you guide me and never let me go. I love you millions. <3

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Author: Jessica PackCalifornia Teacher of the Year. CUE Outstanding Educator 2015. DIGICOM Learning Teacher Consultant. 6th Grade Teacher. Passionate about gamification, Minecraft, digital story-telling, and fostering student voices. Download:Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed